Archaeology Professor Jennifer Ross Writes from Turkey

Professor Jennifer Ross excavated an archaeological site in Turkey.

Jennifer Ross

Program

- Art & Archaeology, Archaeology Concentration (B.A.)

Involvement

Professor

Department

- Art & Archaeology

Degree

Ph.D.

Title

Professor of Art and Archaeology

Part One: Another Year, Another Dig

I’ve just arrived in Turkey for the 20th time in 21 years, meaning I’ve been coming here to dig and research since before most of my current students were born. I’ve also been bringing Hood students here since 2001. This year, I don’t have any students with me, but there are a lot of Hood archaeologists and archaeology alums digging around the world this summer. Workmen ask me about prior students who came in past years, and one of our core team members is the daughter of Mary Jean Hughes (Class of 2008, and staff member in Art and Archaeology and the Honors Program), so the Hood connection remains strong.

I’ve been digging at Çadır Höyük (CHA-dr HOO-yook) since 2003, with a team of American, Canadian, European and Turkish archaeologists from a variety of universities. We live in the village of Peyniryemez (literally, “We do not eat cheese,” which is not true), which feels like my second home. At my desk at the moment, I can hear the bells on the sheep and goats walking down the road in front of our house, while sounds of vegetable chopping come from the kitchen behind me. Soon I’ll smell something wonderful cooking, which the team will come back together to eat around 1:30 p.m., at the end of the digging day. (The afternoon is devoted to work in the lab.)

Our days start early, with breakfast and coffee (mostly brought from the U.S. to sustain us—the national drink in Turkey, despite what everyone thinks, is tea) before leaving for the site at 5:45 a.m. We work until 9 a.m., when we have a “second breakfast”—my students’ favorite meal, I think—of sandwiches, fruit, and cookies. Then work at the site continues for another few hours until it gets too hot to think or see subtle differences in the dirt. Our site was occupied beginning around 5500 B.C., and people lived there until the Byzantine period (A.D. 1000-1100) at least. The mound was created by people building on top of earlier occupations over these 6000-7000 years. Each level represents a different period of time, as the residents used different tools and pots, cooked different foods, and were in contact with different neighbors and political powers. But over that entire time, their landscape must have looked much like it does today—green in the early summer, with ripening grain and abundant pasture lands, and snowy in winter. I imagine the flocks of sheep and goats of 3,000 years ago looked a lot like the ones who graze around the site today, heading out from the village in the morning, and returning to their pens every night, protected by the ever-watchful Anatolian sheepdogs.

I hope to post a couple more updates while I’m here, but I wanted to offer a sense of what life is like on a dig: it can be hot and the power may go out frequently, but the fun of researching with a wonderful team and working alongside our generous Turkish colleagues and workmen makes it all worthwhile. Over the last 21 years, technologies have changed in once unimaginable ways, but out here we also have a sense of timelessness that connects us to the past.

Part Two: Good Teamwork, Good Archaeology

Our archaeological team here at Çadır Höyük, in central Turkey, has now reached its maximum number of people, though we’re still early in our digging season. There are about 30 of us, speaking a number of different languages with a variety of accents. As anyone who has been on an archaeological project knows, one of the most important elements of the work is food. We are lucky to have a wonderful support staff, including a glorious cook who manages two of our four daily meals, and her husband, our driver, who brings a third out to site every morning at 9 a.m. (We’re on our own for our 5 a.m. breakfast.) Below you can see part of our crew at “second breakfast” on site.

Good teamwork is central to good archaeology; while archaeological history is filled with stories of “heroic” Indiana Jones-like figures, like Heinrich Schliemann and Giovanni Belzoni, who capitalized on their own exploits, today’s archaeology is much more interdisciplinary and interdependent. A team like ours includes students new to archaeology, graduate students working on master's degrees and Ph.D.s, paleobotanists, zooarchaeologists, conservators, experts in ancient metallurgy, and professors who are knowledgeable in a wide range of historical periods and questions. I’ve recently been reminded of how much we rely on our entire team to achieve a successful season. While putting together a publication about the trench I’ve been working in since 2005, I realized how many Hood students had a hand in the article.

I used drawings of pottery by Mary Horabik '16, Kristen Squires '16, and Tamara Schlossenberg '16, trench plans by Amanda Shaffery '15, photos taken by Mark Sickle '15, tool identifications by Jeff Geyer '07, and a drawing that reconstructs what we think was going on in the trench at 1000 BC by Mary Jean Hughes '08. Without their contributions, and those of our Turkish workers and colleagues, it would be impossible to do our work, and to let the world know about it. Because it’s expensive to travel and live overseas, we generally spend six to eight weeks working intensively at our site each summer; we live in a sprawling compound with one large house, a lab, storage depot, and a variety of small pre-fabricated houses and tents, and we work 12-16 hour days. It can be both joyous and frustrating at the same time, especially given the close living circumstances and long days. But the results—both what ends up in a publication and the friendships and experiences we share—are immensely rewarding.

Part Three: Ethics and Archaeology

The news story this week that the company Hobby Lobby was fined for illegally exporting looted antiquities from Iraq provides a good opportunity to write about ethics and archaeology, and about the protection of cultural heritage. Concerns about archaeological sites also stand behind some of the recent worries and protests about rescinding the federal protections of sites like Bears Ears in Utah or the archaeological sites on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation where the decision was made to go ahead with pipeline construction.

In places like Turkey, and at archaeological sites across the Middle East, these issues stand in tension with the history of European and American involvement (or meddling, if you will) in politics, and with continuing internal political and economic struggles. Recent looting and destruction of sites in Iraq and Syria by ISIS (about which my colleague Dr. Fred Bohrer has written) have been criticized around the world, but most people are less aware that this looting has provided an income to ISIS fighters, who sell antiquities to middlemen. These objects—including priceless cuneiform tablets, sculpture, and more mundane items like pots—then reach the hands of collectors.

Museums in the U.S. are supposed to abide by the antiquities laws of the countries from which the objects come (the terms of these laws are negotiated by the State Department and international bodies like UNESCO). Although American museums own cuneiform tablets and other items that came from Iraq and Turkey, among other countries, these objects were exported before the international protections went into effect. No museum professional can claim ignorance of these laws, nor can a museum be “unaware” or uncertain of the origin of an antiquity it acquires. Every college and university with museum studies courses and degrees includes extensive instruction in these legal and ethical issues.

Every year, we find at Çadır Höyük tens of thousands of pieces of pottery, dozens of stone and metal objects, and the remains of the hundreds of thousands of meals eaten at the site over the past 7,000 years (including the eggshells we drop during our second breakfast). With very few exceptions, those items stay in Turkey; we study them only while we are in the country, and only with permission of the Turkish government. And that’s how it should be. We are exploring and interpreting the evidence for the long-term history of this place, but it is not our country, nor are the finds our objects. While our work contributes to the understanding of the human past, we must also recognize the sovereignty of the nation and people we become part of each year. There are many conflicting ideas about “who owns the past?” but a good starting point is respect for the people, lands and objects the laws were intended to protect.

Part Four: The Excavation

I’ve been supervising work in the same trench at Çadır Höyük since 2005. It’s about 10 by 8 meters (33 by 26 feet) in size, and has now been dug to over 5 meters (16 feet) in depth. I didn’t do all of that, but I’ve been here for the majority of the work in this particular location.

Archaeologists choose places to dig for a variety of different reasons. Our site was thought to be at risk of flooding in the 1990s when the Turkish government put in a new dam far down our valley. The government therefore asked our team—led at the time by Dr. Ron Gorny of the University of Chicago—to retrieve whatever data they could before the site was submerged. But while we’ve had water come close to the base of the site, the current lake edge is several kilometers away, and we’ve therefore been able to continue digging for all this time.

The site is a mound (höyük in Turkish means “mound”), created over time by repeated construction in the same place. We believe that the first settlers, currently estimated to have arrived around 5500 BC, chose the location to put their houses because there was good agricultural land, plentiful water, and a river running nearby that served as a trade route for goods moving through the region, like certain kinds of stone, eventually metal, and a variety of other materials. Over time, levels of occupation accrued, like a layer cake, eventually producing the present-day mound.

A mound, though, is difficult to dig, because the only way to get into the remains of the ancient town is by excavating both down from the top and in from the sides. At the very top of our site is a Byzantine occupation, dating from the 6th century AD to at least 1100. Archaeologists in past decades tended to be uninterested in the Byzantine remains of the Turkish countryside, considering how well preserved the period was in places like Istanbul and in Greece. But our Byzantine specialist, Marica Cassis of Memorial University in Newfoundland, has successfully argued that what went on in cities like Istanbul was very different from life in the countryside, where our site was. Thanks to excavations on the summit of the mound, and in a lower settlement on a terrace next to the mound, we now have a significantly better idea about how Byzantine villagers lived, and how they adapted to the political and religious changes that dominated their centuries.

My trench, USS (Upper South Slope) 4, has remains of the Iron Age, dating from 1200 to 400 BC. Because it holds a “continuous sequence” (an apparently unbroken series of occupations) that span this nearly 1000-year period, the site is unusual for the region, and the evidence that comes from the trench is invaluable for reconstructing historical, political, social and technological changes over that time. The Iron Age began when the great empire that ruled Turkey during the Late Bronze Age, the Hittites, fell to a variety of forces. At many Hittite sites, there was a gap in occupation, suggesting that residents abandoned their homes due to fighting or instability. But something different was happening at Çadır, and while the inhabitants may have felt some rumblings of trouble (the Hittite capital is just 70 kilometers away), they adjusted quickly and continued to thrive.

When we reached the Late Bronze Age levels at the bottom of my trench last year, we had accomplished our goals for this part of the site. Therefore, I have not been digging in the trench this year, but rather completing some drawings and studying the finds. I’ve also had the opportunity to “float”—to invade the trenches of other supervisors in order to “help” them (I hope) with problems of excavation or interpretation. We have always made an effort to make sure our students work in each trench at the site, as every area has its own questions to answer, and every supervisor can teach different techniques of excavation. I’m lucky to also have colleagues open to welcoming me into their trenches and time periods, to share their experience and understandings of the mound. As usual in archaeology, our collaborative work is the main way our knowledge of the past can increase.

Photos from the Excavation Site

The Mound at Çadır Höyük

View from the Mound at Çadır Höyük

Laurel Hackley, daughter of Mary Jean Hughes '08, instructing a pair of Turkish college students about digging.

The team gathers for their second breakfast.

A room in the lab where people are working on their notebooks and drawing pottery.

A student from the University of Washington teaches a group of British students about making and drawing pottery.

Excavated Pieces

Ross and Sharon Steadman, the project’s codirector, sorting pottery. 2012.

Madelynn Von Baeyer, our paleobotanist, recovering seeds using a “flotation device.” 2012.

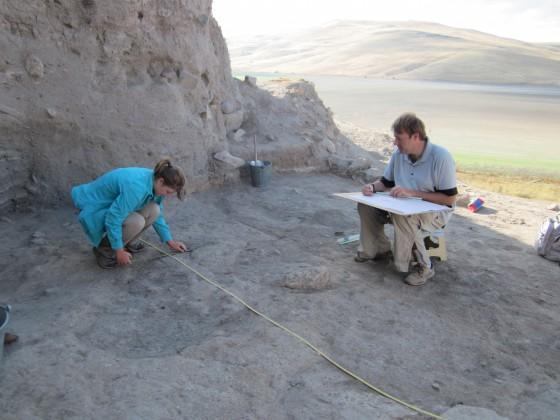

Amanda Shaffery '15 drawing with Tim Buttram of the University of New Hampshire in the trench in 2013.

Drone photo of the site taken in 2014, with the Byzantine material at the top and the trench just below.

Ross and Mary Jean Hughes '08 in 2005, the first year she dug in the trench.

Are you ready to say Hello?

Choose a Pathway

Information will vary based on program level. Select a path to find the information you're looking for!